Is Color Photography an Art?

There is an ongoing debate about whether color photography is an art form, or simply a craft. In the arts community, the decision as to whether a form of expression is an art rests with museums and art critics. For museum curators, it is widely accepted that black-and-white photography reached the level of art with the work of Ansel Adams. I have studied his work and writings, along with that of other great photographers. What he accomplished in the world of black-and-white photography stands as something to work toward in my chosen medium of color. Some famous color photographers whose work I admire are Eliot Porter, Charles Cramer, and David Muench.

While black-and-white photography from the best photographers has been collected and exhibited on the level of fine-art paintings, color photography has been a different matter. Since it arrived later than black-and-white, it is still in the process of becoming accepted by museums as a legitimate art form. The earliest color processes had poor color reproduction and were limited as a means of expression; also they had limited archival stability. This early history contributed to a skepticism toward acceptance of color photos as art. Since color photos often attempt to reflect the reality of a scene many art critics view them as merely documentary, not expressive.

Museum curators often focus on the abovementioned fact that color photographs have a shorter archival life than properly prepared black-and-white images. While true, high-quality color inkjet and optical prints have a lifetime of 100 years or more when stored properly. Furthermore, many recognized art forms have much shorter lifetimes. Performance art and mixed media collage are two examples. Now that photography is moving toward digital representation, in theory a color photograph can have an infinite lifetime it there is available technology to view and print it.

Fundamentally, art is the communication of emotion. Color has played an important role throughout history in such communication. As art evolved from primitive times, one of the first innovations was the use of color in sculpture, jewelry, and painting. A photograph of a red rose evokes love. That simple option isn't available to a black-and-white photographer who wants to express this emotion. Anyone in the upper echelons of the art establishment who denies that color photographs cannot be as expressive as black-and-white ones is denying this simple fact (unless that person happens to be severely color-blind and cannot see color at all.)

Since a color photographer is writing this, you already suspect my answer. The color photographer has many means of bringing expression into a scene; the selection of camera position, lens focal length, use of filters, depth of field, film type, exposure, composition, and shutter speed all figure into the image that is produced. During printing, the color photographer has control of contrast, density, color balance, and saturation to convey personal expression. Beyond these technical considerations there is the type of lighting, weather conditions, choice of subject, timing, and ability to "see" a photograph rendered on film and in the final print before setting up a camera. This skill is something Adams called "pre-visualization". The ability to pre-visualize a photograph applies equally to black-and-white and color processes. Pre-visualization involves an intimate understanding of the characteristics of light, the film, chemistry, and printing paper, so that a photographer is able to use exposure, development, and other techniques to control the process of recording a scene on film in a way that preserves the visual information of the scene that is desired to be expressed in the print.

On a similar level to pre-visualization, I believe, is the ability to anticipate a photograph, that is, to pre-visualize a scene before it happens. For the large-format camera where setup times can be as long as 30 minutes this is a critically important talent. Although Ansel Adams and other famous black-and-white photographers don't discuss anticipation it is clear from their work that they had this ability.

Two other important innovations Adams pioneered are customized film development to control contrast, and the Zone System, a system of exposure measurement useful in the process of pre-visualization. While custom development applies to color photography in only very limited ways, the Zone System is quite useful. It is hard to believe that custom development could be the one thing that defines black-and-white photography as an art, and sets it apart from color in this regard.

Most people assume color film is fundamentally different from black-and-white film and by its nature unsuited to the kinds of exposure and contrast manipulations black-and-white photographers practice. That couldn't be further from the truth. Color film evolved from black-and-white film, and in reality consists of three separate images: a blue image, a green image, and a red one, sandwiched together. Some modern films have additional color layers. Each of these color layers can be thought of as a separate black-and-white image. In fact, many black-and-white photographers (Adams included) then and now, take photos with red, green, yellow, or blue filters under certain conditions to change the appearance of the image recorded on film. They are practicing a portion of the process that happens today with color film.

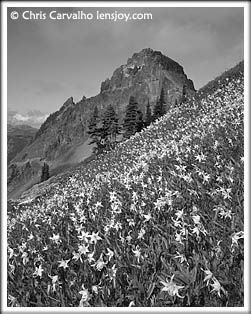

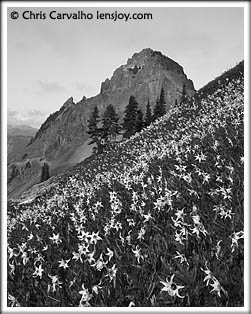

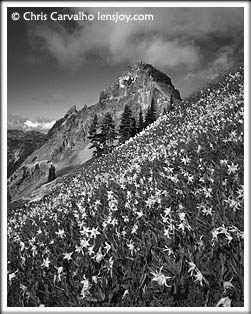

Let's look at a color photograph and the component red, green, and blue images. These images are easily examined in a scan of the film as shown below:

Individuality, color image

|

|

|

|

Red Channel |

Green Channel |

Blue Channel |

A color photographer has the ability to manipulate the contrast and exposure of the three images independently. The finest color photographers often use color masks as a tool to achieve control of the printed image. Such masking is a painstaking process and fraught with more effort than the custom exposure and development techniques for black-and-white negatives that Adams pioneered. Fortunately, with the arrival of digital technology color masking can easily be done in Photoshop with none of the problems the technique had in the wet chemical darkroom.

Seen from this perspective there is essentially no difference between the work a color photographer does to create an image versus the black-and-white photographer. Indeed, the color photographer's job can be seen as three times as difficult since there are three different monochrome images to keep track of in managing the perception of color.

Beyond that, it is even possible to create entirely new black-and-white images from the three color layers in film by combining them in different ways. The resulting black-and-white photo isn't color, but it couldn't be created without the use of color film (or by taking three separate black-and-white images through colored filters.) The example below shows one of an infinite number of possible combinations of the red, green, and blue layers of the film, along with selective contrast and brightness manipulation in different parts of the image to produce an expressive result:

In this example, I created a Channel Mixer layer in Photoshop, set it to monochrome mode, then combined 67 percent of the red channel, 65 percent of the green channel, and subtracted 22 percent of the blue channel . I increased the contrast of the sky and distant mountain, and darkened the foreground slope with the flowers to produce a final image.

While my black-and-white version of Individuality is something I would gladly print and hang on my wall, what sets the color image apart is the red Indian Paintbrush flower in the foreground. It is the real subject of the image and expresses the message I wanted to communicate. There is no way to produce a black-and-white print that communicates the same message because red, when rendered in black and white, is not a tonality that catches the eye when surrounded by white flowers. So it's clear from this example that color provides an expressive option that is unavailable to the black-and-white photographer.

Many beautiful color photographs are equally beautiful in monochrome. So a color photographer often sees in black-and-white as well, though the choice may not be a conscious one. Certainly there are differences and some color photos are not appealing in their monochrome versions, but the fact that the original scene was in color to begin with means that it likely looked good in color when a black-and-white photographer saw it!

Evidence is one thing; acceptance in the critical and museum communities is another. I believe color photography is art. It has become widely accepted in publishing and consumers purchase millions of color images in books, magazines, cards, posters, and prints each year. There are many galleries that exhibit only color photography. Color photographers continue to express their art in the hope that critical acceptance will someday follow. I believe it to be more a matter of time than of waiting for a person like Ansel Adams to create an equivalent breakthrough in the medium of color. There are many excellent color photographers that have already created great and timeless images and are helping pave the way toward recognition for all of us who work in the field. I hope this discussion has opened up insights for the reader about the relevance of color photography as a means of artistic expression.

For my own work, I have chosen to follow where my vision takes me and not to fight a battle of critical acceptance. To fight for acceptance would bring the desires of critics and museums into my creative process. I am not here for them. I am here for nature, and to show people what nature has to say is at the heart of my work.