This is the full version of the article. Click here to return to the blog's home page.

Wake Up And Smell the Smoke

The 2017 Eagle Creek Fire teaches lessons in fire policy and involving the public in crafting it.

Entry 19: October 19, 2017

This article was updated October 22, 2017 with additional

information.

|

|

In the classical Greek legend of Pandora's Box, Zeus was angry

with Prometheus for giving people fire. He sent a beautiful woman, Pandora, down

to earth with a box, saying it must never be opened. She married Prometheus'

brother. Curiosity eventually overcame Pandora and she opened the box,

unleashing troubles of every kind on humans. It was the gift of fire that

started it all.

The 2017 Eagle Creek Fire in the Columbia Gorge began Saturday on a hot Labor Day weekend, when hundreds of hikers seeking shade and a cool river to splash in headed up one of Oregon's most popular trails. Most of the summer, the path was closed several miles to the south because a fire was burning in steep terrain that started near a trailside camp on July 4th. Named the Indian Creek Fire, the Forest Service had been fighting it for almost two months by dropping water on it from helicopters. A source in the agency said that fire was likely caused by fireworks but the perpetrator hadn't been identified.

On September 2 a group of teenagers was hiking near Punchbowl Falls, a popular spot with a picturesque waterfall and streamside access off the main trail. A witness reported seeing one of the boys toss a lighted firework into the canyon, and smoke started rising almost immediately afterward. The witness summoned law enforcement at the trailhead, and police questioned the group before releasing them.

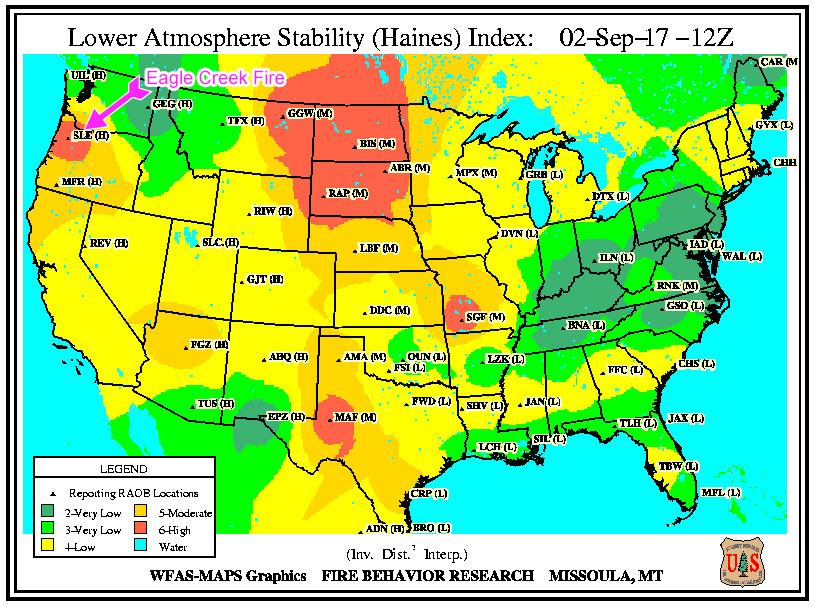

There was another difference that day. It had been a hot, dry summer. The forest was a tinderbox ready to go up. Compounding high temperatures, hot winds created an unstable atmosphere perfect for large fire growth. Foresters know this and plan for it. A map of the Haines Index, a prediction scale ranging from two to six with six being intense fire growth conditions, showed Eagle Creek was in the bull's-eye.

Map

of the Haines Index on September 2, 2017 (available from https://www.wfas.net/index.php/search-archive-mainmenu-92)

The time was about 4 pm, and a clock started ticking. When a fire starts in a dry forest in windy weather, there are just a few short hours to put it out before it grows rapidly out of control. Those hours are the time to hit it with everything you've got, a phase called the "initial attack." Tick: The Forest Service diverted helicopters from the Indian Creek Fire to help with the new one. They helped assist 150 trapped hikers and campers near the fires, and dropped water to try to slow the fire's spread.

Tock: In two hours, the fire raced up a 3,500-foot ridge, producing 300-foot flames. Pandora's Box had been opened, and nothing could be done to put back the trouble. In only 16 hours after the fire started, it grew to 3,200 acres. The critical time to stop it had already passed. Once a fire reaches that size, helicopter water drops are like trying to put out a bonfire with a thimble. Over the next two weeks, the fire expanded to 48,000 acres (link to video of fire's progression) and cost over $18 million to fight. As of this writing, it's still not out so the final figures are unknown.

A helicopter

ferries water from Wahtum Lake to the Indian Creek Fire

The impacts from the fire are only beginning to be understood and will affect the region for decades to come. Residents were evacuated from homes, businesses lost money and laid off employees, transportation was shut down, Interstate 84 lanes are reduced at a landslide-prone section causing traffic delays, hiking trails are closed and likely won't open until summer of 2018, major tourism draws such as Multnomah Falls and the waterfall segment of the Historic Columbia River Highway are closed, landslide and rockfall risk are heightened until stabilization work and natural processes take their course, and habitat for rare plants and salmon has been degraded. We narrowly missed a major fire in the Bull Run Watershed, the source of Portland's drinking water supply. For likely more than a year, the Oregon side of the gorge will be economically depressed since recreationists will take their business elsewhere.

After the Eagle Creek fire, a logical question to ask is, "What is the fire management plan for the Columbia Gorge?" The answer is hidden behind layers of government, and transparency has worsened in the past decade. A 2008 version still exists as a forgotten public document online. Now, it's very interesting reading indeed. It appears the plan was never intended for the public to read as it contains corrupt font data. It can't be read on Windows PCs, but Apple software can decipher most of it. It's a treasure trove of information.

Since then, the Forest Service moved to a computerized planning system. It's not accessible to the public. So there's no way for us to know today's fire management strategy, and unclear if there's any process for interested stakeholders to suggest changes. Now that we know the damage an uncontrolled fire in the gorge can do to the region's economy, habitat, and recreational resources, it's essential for the public and representatives of all affected groups to be involved. The forthcoming inquiry into the response to the fire must address some key questions. While Forest Service officials are tight-lipped, I've obtained some information through anonymous sources.

The current plan calls for full suppression of all fires within the Columbia Gorge Scenic Area. The 2008 plan defined full suppression as containing 95% of all wildfires during the initial attack stage of 24 hours or ten acres. With Eagle Creek, that did not happen. Why wasn't containment reached in that period? This fire had the best possible notification that it started: Eyewitnesses immediately hiked out and contacted police. Helicopters were diverted from the nearby Indian Creek fire to dump water on the new fire. That response was ineffective. The Indian Creek fire started July 4, and burned all summer. With two fires in the same season that could not be suppressed during initial attack, there is a serious flaw in our firefighting strategy. What must change so a similar fire will be put out?

Sources in the Forest Service say that there was likely nothing that could be done, even with the best equipment available immediately, to put out the Eagle Creek Fire owing to the conditions that day. Whether or not this is true, there are certainly many things we could do that might have prevented the fire from starting in the first place.

The plan's authors knew the gorge's fire history: "From early September through mid-October the west end of the gorge offers the best of all worlds from a fire's perspective. The tremendous fuel loading of a west side forest coupled with hot and dry wind and incredibly steep terrain make for some of the most spectacular burning conditions the Pacific Northwest has to offer." Fire risk maps rate Eagle Creek as high to extreme, the two most dangerous categories. With this risk and fire history well known, why was the public allowed in the area?

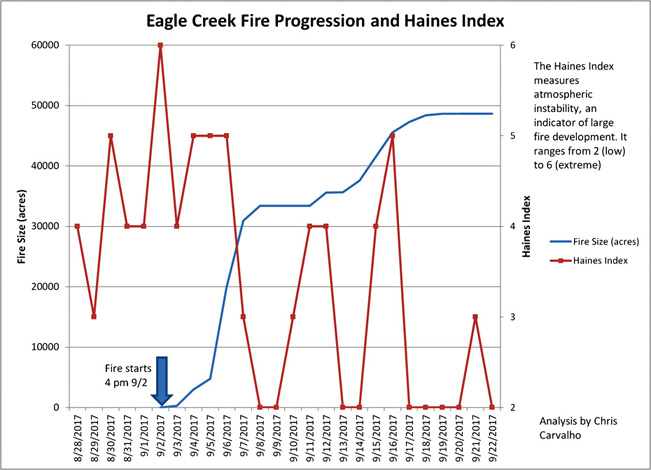

There is a precedent for closing trails at times of high fire danger. Portions of the Klickitat Trail are traditionally closed from June through mid-October. We could do something similar in the Columbia Gorge, possibly closing trails when indicators such as vegetation moisture and the Haines Index predict rapid fire growth. Charting the index and the fire's size below shows the fire grew quickly on days when the index was high, and growth leveled off when it dropped. What saved us from a much more dangerous situation was the cooler, damper weather of early fall. After five days of high numbers, the index dropped and there was only one more day when it rose as high as five. If this fire had happened a week or two earlier, we might have ended up with more than 100,000 acres burning on both sides of the Columbia Gorge. Luck should not be a major component of our fire management strategy.

Chart showing Haines Index and daily fire growth

The plan summarized past causes of fires and their frequency. Ninety-nine percent were from human causes. Burn bans were in effect late this summer, accounting for 56% of total historical risk. In 2017, fireworks were the cause of three fires in the gorge. Should we consider a total fireworks ban in Oregon and Washington?

Fuels reduction is frequently proposed to reduce fire risk. In much of the Columbia Gorge, it's not practical or even possible. Wilderness lands can't have roads or motorized equipment in them and our rainforest is naturally dense stands of Douglas fir, cedar, and hemlock. This year's fires were the result of a very dry summer in a forest that was healthy, yet vulnerable to human-caused fire. Thinning this forest would destroy critical habitat, decrease slope stability, and increase erosion. It's not a feasible strategy. Trees are not the problem, people are.

Since a minor allegedly caused the fire, Oregon law limits parental liability. Parents are liable for up to $7,500 per claimant. Fire agencies can only recoup $5,000 of their costs from parents. For both children and adults, we need to examine if there is enough of a deterrent in place. Should there be stiffer penalties for arson, clearly posted at all recreation sites?

A popular question to officials was why didn't they use supertankers, jumbo jets that can dump almost 20,000 gallons of water or retardant on a fire? The answer is complex and takes an entire article to explain. A simple calculation that appears to have been overlooked strongly suggests they could have helped. The fire cost about one million dollars per day to fight, and a supertanker costs around $120,000 per day to operate. When estimated economic impact is added to firefighting cost, using a supertanker for 12 days pays off if it shortens the fire's duration by one day. Restoration cost will add greatly to the final cost of the fire. If the fire's size could have been reduced through supertanker use, restoration cost would also be less, making a compelling case that they should have been deployed.

I want to clarify that I'm not laying any blame on particular individuals. There is a combination of misguided policy and funding issues, both from many levels of government, that have caused officials to respond to fires more timidly than in the past. Rapid growth in our region has strained trails to the breaking point, and we haven't kept pace with the added demand and increased danger from many more people in the woods, some of whom are unfamiliar with our area's fire history. We've seen the pendulum swing from policy that put fires out immediately without regard to the fire's potential benefits, to now believing that "let it burn" is a better way to manage them without considering the fire's harmful impacts. Fire crews have done an exemplary job of protecting lives and property this time, and that's good. But the flip side is that habitat and recreation resources have taken a gut punch. Many have asked to publicly name the teenager who threw the firework into the canyon. While justice feels good, it's important to remember that our fire policy is the root cause. It created a situation where one careless person could destroy a vast area loved by millions of people. If it hadn't happened September 2, it would happen in the future from any one of a number of causes without improvements to our response and prevention plans. We could blame Prometheus, but the best thing to do is look ahead and ask what needs to change, and insist that everyone affected has a seat at the table to create future policy.

This year, Oregon has spent $340 million on firefighting costs. In the gorge's rugged terrain, air drops are the only known option to effectively fight fire. If we need better equipment such as larger air tankers, we could have easily purchased them for a fraction of that money. It's time to wake up and smell the smoke. We need a thorough, open review of fire prevention strategy, response planning, and budgeting for the Columbia Gorge, and the entire state.

Chris Carvalho has a Bachelor of Science degree in chemical engineering from the University of California at Berkeley. He is a photographer and blogger on public policy, environmental, and conservation topics.