This is the full version of the article. Click here to return to the blog's home page.

Leave No Virtual Trace: Thanks to social media sharing, mobile phones are now weapons of mass wildland destruction

New ethics needed to address Internet-enabled mobbing of natural areas

Entry 21: April 15, 2018

By Chris Carvalho

Less than a quarter-century ago, recreationists had only paper maps, guidebooks, and word of mouth to discover new places to visit.[1] A few online articles were beginning to appear. Then the Internet snowballed. In 2018 smartphones are almost universal, putting cameras, data access, global positioning, search engines, and instant social media sharing in the hands of nearly every tourist and hiker. This profound change has made it possible to show a sensitive landscape to a multitude of people at the push of a button, complete with driving instructions. The Internet’s viral quality of unlimited replication can multiply one picture to millions of copies and views in a few days. As a result, delicate places have become overrun by selfie-snapping visitors eager to document their trip to a cadre of virtual “followers.” The integration of these technologies into smartphones has weaponized our mobile devices into tools for wildland destruction.

Leave No Virtual Trace Principles

Download

high-res image

Before the arrival of the Internet and smartphones, we had to do real research to find places to enjoy solitude and the beauty of nature. It cost us money and time to do it, and those costs put a brake on visitation impact that kept wildland overuse in check. In today’s world, finding information is fast and free thanks to search engines such as Google, whose original motto of “Don’t be evil” was dropped in 2015.[2] Libraries, bookstores, and hiking clubs used to be where we went to gather hiking trip ideas. Now, they are largely irrelevant.

Readers shouldn’t get the impression of a conspiracy here. What’s happened is that a number of enabling technologies were invented and combined over a relatively short time period. These developments had the unintended consequence of greatly multiplying the number of people who can advertise and promote the beauty of a natural site to a hungry public anxious to find new destinations, and it’s happened at a speed that far exceeds anything we might have imagined.

If we consider the rapid pace of change in only 25 years in the timeline below, the next 25 years could thrust us into a situation where serious damage to wild places may be irreversible. We need to take action now before it’s too late.

What can be done to address the problem?

Hikers now consider mobile phones the Eleventh Essential to summon help

in an emergency. What’s missing is

guidance on limiting the impact from social media sharing.

We need a new addition to the code of outdoor ethics, part of what we

know as the Leave No Trace principles. The

idea of “Leave no Virtual Trace” with the hashtag #LNVT is that new ethic.

We need it because it’s no longer enough to hike, bike, or ride our

stock responsibly and with minimal physical impact.

Even when we clean up after others, we need to take responsibility for

the real-world impact of sharing our experience online, because we  can’t be

sure what others might do if they visit a spot based on our social media

posting. Leave No Virtual Trace

means, “Don’t post photos, routes, or coordinates on social media of any place that

would be harmed by increased visitation.”

The slogan isn’t my creation; it came from a fellow member of an online

hiking discussion forum who suggested it in a thread I opened on this topic.[3]

can’t be

sure what others might do if they visit a spot based on our social media

posting. Leave No Virtual Trace

means, “Don’t post photos, routes, or coordinates on social media of any place that

would be harmed by increased visitation.”

The slogan isn’t my creation; it came from a fellow member of an online

hiking discussion forum who suggested it in a thread I opened on this topic.[3]

I shared this idea with Dana Watts, the executive director of the Leave No Trace Institute for Outdoor Ethics. Her response was measured, believing that no new principles beyond what's currently adopted are needed. Rather, she felt social media sharing can be related to the organization's existing principles of Leave What You Find and Be Considerate of Other Visitors. I don't think this approach is enough to meaningfully create the changes that are needed. I've included her response below in the Appendix.

Other measures that might help include the following:

|

Advance warning by land managers that overused areas will be closed or visitation restricted if social media sharing isn’t curtailed, followed up with action if warnings are ineffective. | |

| Incorporating the Leave No Virtual Trace principle into the ethical code of the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics (http://lnt.org/). | |

| Standard signage that’s used worldwide at sensitive sites to advise visitors to curtail posting on social media. | |

| Government and conservation groups could create an open database of areas with excessive impact. Social media companies could check the location of posts against the database and warn the poster of the risks and consequences of sharing, as well as remove geotags from posted photos. | |

| Public education campaigns to make people more aware of how social media sharing can damage habitat, and ask users to go back through their timelines and take down photos of overused areas to reduce future impacts. | |

| An aggressive campaign of charging access fees at overused areas to discourage visitation, with fee dollars devoted to site restoration and construction of new trails to spread out the impact | |

| Social media users can respond constructively when someone’s postings endanger wildlands. | |

| Voters and conservation groups can put pressure on elected officials to restore lost funding for land preservation and recreation development. | |

| Land managers should work with social media companies to enable donations from within applications when sensitive sites are being viewed to create a new funding source for protection and restoration efforts. | |

| Discouraging people from posting GPS tracks of routes that aren't on established trails. Most land managers ban unauthorized trail construction, but a GPS track can do as much damage through the repetitive trampling of multiple visitors following it. |

|

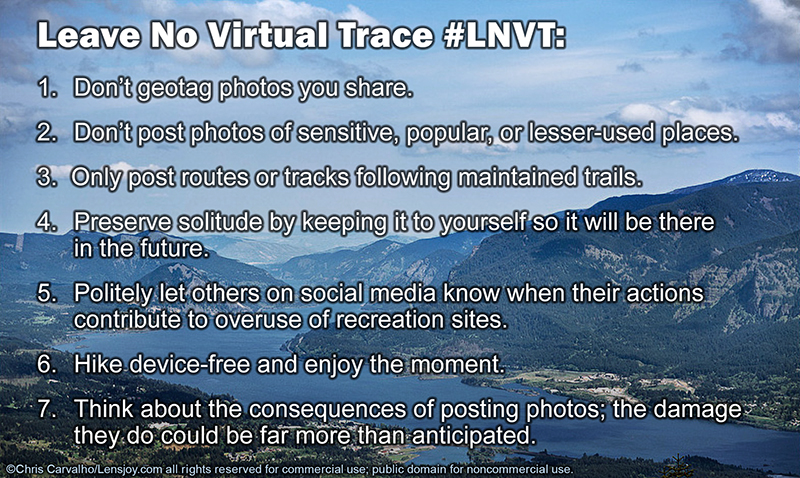

Principles of Leave No Virtual Trace #LNVT: 1. Don’t geotag photos you share. 2. Don’t post photos on social media of any place that would be harmed by increased visitation. 3. Only post routes or tracks following maintained trails. 4. Preserve solitude by keeping it to yourself so it will be there in the future. 5. Politely let others on social media know when their actions contribute to overuse of recreation sites. 6. Hike device-free and enjoy the moment. 7. Think about the consequences of posting photos; the damage they do could be far more than anticipated. 8. Remember that when photos or videos are shared they can multiply views and visitors uncontrollably. Fame is not worth the damage that could result to a fragile area. |

As little as ten years ago, recreation officials were worried that hiking was in decline and would never recover, forcing funding cutbacks and reducing the acreage of protected land. In some ways we can be thankful that the rise of social media has produced the opposite problem: too many users. Unfortunately funding cutbacks did arrive, courtesy of governments that have diverted taxpayer dollars from public lands to other wasteful expenditures.

Social media sharing can be good when it rallies public support to protect threatened habitat. What’s lacking today is a nuanced understanding of when to use it properly and when to turn off the smartphone in the interest of keeping secrets a secret. The lure of online popularity is a calculated enticement that social media companies use to eliminate any discretion on the part of those who post. I’m not optimistic that people will learn to resist that temptation.

While some argue that sharing photos is harmless and it’s irresponsible people who do the damage, it’s important to realize that a considerate hiker who leaves no physical trace yet shares the experience online opens a door to impact from any number of users who might view the post and visit later. Social media sharing makes us feel isolated from the impacts of many who follow our footsteps in the future, but that’s a false perception. Opponents of leaving no virtual trace say no one should control the actions of others because it violates one’s personal freedom and responsibility. Yet, most ethical hikers would never invite a group of strangers along on our trip, expecting no harm will come from it. Even if we don’t see the impact from sharing on the day of our trip, a year later it will be obvious what happened. It’s precisely because we can’t control others’ actions that it’s not wise to post our photos online.

Another argument I’ve heard is that asking people to not post will encourage the opposite as an act of defiance. I’m not convinced. Most of us obey “do not photograph” policies at museums, concerts, and other events. Museums originally said it was to limit fading from flash photography, but most cameras today are so sensitive that flash isn’t used any more. The real purpose of these policies is to get people to pay to attend in person. Asking the same thing of hikers in order to limit impact is a more noble justification and it would likely be quite effective.

We need to consider that there have been many threats to wild areas: motorized travel, logging, litter, livestock, energy development, mining, housing, etc. When each was new it wasn't believed to be a problem but when it reached critical mass, the threat was recognized and required regulation to keep it controlled. The impact of Internet social media is quite possibly another in this long line of threats. It's still early, but the Internet's rapid pace of advancement is forcing us to recognize the problem quickly and respond before it's too late. Hopefully ethics rather than regulation can be the solution, but history says otherwise. Because solitude is a resource worth protecting, we all must learn to Leave No Virtual Trace.

| While You Were Out Hiking |

|

A timeline of developments contributing to social media’s impact on natural areas |

|

August 6, 1991: The first web page was created at http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html |

|

September 4, 1998: Google was founded |

|

May 2000: Dept. of Defense disables GPS Selective Availability: http://www.gps.gov/systems/gps/modernization/sa/ |

| June 11, 2001: EarthViewer 3D, which will become Google Earth, is released, offering free access to satellite imagery |

| 2002: GoPro, a wearable video camera manufacturer, is founded |

| Feb. 4, 2004: Facebook founded |

| March 2004: Nokia introduces a phone with a 1 megapixel camera, the 7610. |

| February 14, 2005: YouTube founded |

| 2006: GoPro introduces the Digital Hero wearable camera, capable of recording 10 seconds of video |

| March 21, 2006: Twitter founded |

| June 29, 2007: The iPhone was introduced |

| 2009: The US Geological Survey began the release of a new generation of topographic maps online for free download |

| June 12, 2009: Analog TV signals in the USA cease, ushering in high-definition digital video. |

| September 21, 2009: Gaia GPS is introduced, turning a smartphone into a GPS and geotagged camera with instant publishing of routes, for free. |

| 2010: The Parrot AR Drone, a smartphone-controlled quadcopter for consumers, is introduced at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. |

| October 6, 2010: Instagram founded |

| October 31, 2011: Global population reaches 7 billion |

| March 21, 2012: Twitter celebrates its sixth birthday, with 140 million users and 340 million tweets per day |

| 2013: GoPro sales reach $1 billion |

| December 2014: 98% of the US population is covered by 4G networks: https://www.gsmaintelligence.com/research/2014/12/mobile-broadband-reach-expanding-globally/453/ |

| August 27, 2015: Facebook reaches 1 billion users in a single day |

| April 26, 2017: Instagram reaches 700 million active users, doubling in two years. |

Appendix: Dana Watts' response:

December 12, 2017

Hello Chris-

This topic has been front and center lately for many people, including Leave No Trace. My colleague Ben Lawhon responded recently to a similar request for the creation of an 8th principle that would directly address social media. This response accurately captures The Center's position on the issue and I hope is helpful:

Thank you for your support of Leave No Trace, and for your email regarding the use, and potential consequences, of social media. This is an issue that we have been hearing more and more about over the past year, and it’s something that we’re actively working to address.

There is little question that social media plays a role in promotion of various outdoor locations, and in some cases, has led to significant biophysical and social impacts. It’s logical to ask, “Would this place be as impacted as it is now had it not been for Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, or Pintrest?”[sic] Social media, like any tool or technology, can be a force for good or it can have the opposite effect. What if every social media post also included a message of stewardship? Think how different things would or could be if this were the case.

As technologies have evolved over the past 15 years we have explored the potential impact to the outdoors, and in some cases, have addressed such issues with Leave No Trace. For example, in the early 2000s when handheld GPS units were made more accurate, more reasonably priced, and smaller, there was justifiable concern about how these devices, and associated activities such as geocaching, could potentially impact the outdoors. Another example dates back to 2013 when drones began appearing on (or above) public lands. Drones are relatively inexpensive and easy to fly. As such, there were genuine and valid concerns about the use of such devices on public lands, which can impact solitude and wildlife, and present privacy and safety concerns. A final example from just a few weeks ago involves the use of personal locator beacons such as the SPOT or the ARC ResQLink, which can be life-saving devices or lead to costly, impactful, and unnecessary rescue operations where the user has simply run out of beer. In each case, we have been asked to provide specific Leave No Trace guidance by adding additional Principles. In some cases, we have provided guidance (geocaching/GPS use) under the existing Principles and in others we’re still working on the most appropriate strategy for addressing issues arising from such rapidly evolving technology.

Because the current incarnation of the 7 Leave No Trace Principles have been in place for nearly 20 years, we don’t take discussions of significant changes lightly. Such discussions are imperative at times but also need to be strategic, thoughtful, and measured. In the case of addressing appropriate use of social media, we feel that it is possible and necessary to tailor existing Leave No Trace information for this purpose rather than creating a new Principle out of whole cloth. There are two current Leave No Trace Principles under which social media can be addressed: Leave What You Find and Be Considerate of Other Visitors. For each Principle, the message about social media will encourage outdoor enthusiasts to stop and think about their actions and the potential consequences of posting pictures, GPS data, detailed maps, etc. to social media. Furthermore, we urge people to think about both the protection and sustainability of the resource and the visitors who come after them. We generally refrain from explicitly telling people what to do in the outdoors, especially in the context of more ethical issues such as the use of social media. The primary reason for this is that Leave No Trace isn't black or white, right or wrong. It's a framework for making good decisions about enjoying the outdoors responsibly, regardless of how one chooses to do so. That said, if we can simply encourage folks to stop and think about the potential impacts and associated consequences of a particular action, we can go a long way towards ensuring protection of our shared recreational resources.

As we have thought through this issue we’re left wondering what the future will bring in terms of technology, communication, and outdoor recreation. Will posting pictures to social media be a thing of the past in five years? None of us know. However, we do know that it is currently contributing to some level of impact in the out-of-doors, which is something we are actively addressing. Not only will we encourage responsible use of social media but we will also embolden and inspire social media users to promote and provide a message of Leave No Trace stewardship with any and all relevant post about the outdoors. Social media, if used the right way, is a powerful tool that can motivate a nation of outdoor advocates to enthusiastically and collectively take care of the places they cherish.

Please know that we are actively working to address the intersection of social media and the outdoors through the appropriate channels. As such, we welcome further input, discussion, and constructive feedback.

Again, we appreciate your sincere commitment to Leave No Trace. It is individuals like you who are making a real difference for our shared lands.

Best,

Dana Watts

Read more from the Leave No Trace Institute on this topic at their blog.

References:

[1] Manjoo, Farhad. “Jurassic Web: The Internet of 1996 is almost unrecognizable compared with what we have today.” http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/technology/2009/02/jurassic_web.html

[2] Basu, Tanya. “New Google Parent Company Drops ‘Don’t Be Evil’ Motto” Time. http://time.com/4060575/alphabet-google-dont-be-evil/

[3] Carvalho, Chris. “The Quiet Pledge: What to do about overcrowding.” http://www.oregonhikers.org/forum/viewtopic.php?f=7&t=24810

Further Reading:

Knepper, Brent. "Instagram is Loving Nature to Death." The Outline. https://theoutline.com/post/2450/instagram-is-loving-nature-to-death. November 7, 2017

Solomon, Christopher. "Is Instagram Ruining the Great Outdoors?" Outside. https://www.outsideonline.com/2160416/instagram-ruining-great-outdoors

McHugh, Molly. "Loved to Death: How Instagram Is Destroying Our Natural Wonders." The Ringer. November 3, 2016. https://www.theringer.com/2016/11/3/16042448/instagram-geotagging-ruining-parks-f65b529d5e28#.evqrskkyg

Chris Carvalho has a Bachelor of Science degree in chemical engineering from the University of California at Berkeley. He is a photographer and blogger on public policy, environmental, and conservation topics.