![]()

In the spring of 2002 I returned to the Southwest to photograph the area's spectacular landscape. I traveled with David Trumper, a friend from England I met in the area two years earlier and is also an avid photographer. It was a marvelous trip and having a friend along made it possible to visit places I'd be wary of seeing alone. My creativity benefited from having another person to bounce ideas off and to collaborate with on composition and lighting.

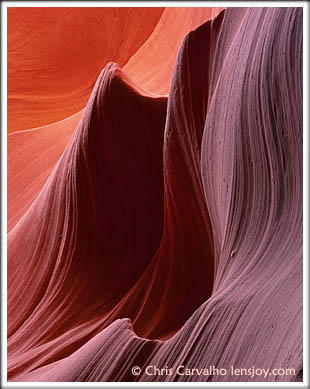

We spent several days in slot canyons, including the lower and upper Antelope canyons. These are now well known among photographers and can be challenging to photograph. There is constantly changing lighting, large tour groups, flashbulbs going off from other people's cameras while one is taking a long exposure, and the opportunity to excitedly review the film from the trip--only to find that I missed spotting another person's foot or tripod leg in a carefully composed scene. The rewards are worth it. Though the rocks appear frozen in time, they do change on a geologic time scale. Flash floods carve the swirling sandstone walls of the canyons over thousands of years and create formations that can only be described as the finest examples of Nature's art. Light reflecting off the red and purple sandstone creates unusual colors, leaving me spellbound at times.

The scene above is from lower Antelope canyon. David and I watched it over two days and found the time when the light would be the best. The results on film were better than I expected. I enjoy the simplicity and graceful curves that remind me of waves of water, but with the very unexpected red color palette.

If you plan to photograph slot canyons, here are several tips. Exposure times will likely be long, so know your film's reciprocity characteristics. The dim light will render all but the best digital cameras ineffective. Don't use flash; it will overwhelm the soft colors and create problems for anyone with a lens open at the time the bulb goes off. Bracket liberally unless your light meter indicates the scene will be easy to expose. Be wary of highlight and shadow areas in your composition; their light levels will likely be so different from the glowing rock that a shot is not worth taking. Your eye will see more in the shadows than the film will, so try to make compositions with even lighting whenever possible. Have patience. Often I would visit a canyon a day in advance and take notes of the places to be and the times when the light was best, then return a second day for the shooting, knowing exactly when and where I needed to be. Plan for the unexpected. Sand can become windblown and fall onto cameras and equipment, so bring something to cover the camera while it's on the tripod. Focusing in the dark is difficult. I carried a flashlight to help with adjusting the camera in the deep shadows.

On your first trip to the area, don't expect too much. You will need to gain some experience before seeing the results you want. After six days spent over two trips to Antelope canyon, I still have only five images that I am satisfied with. The first two days I shot a lot of film but did not produce anything worthwhile. After that, I learned to be more selective. Visit the area at the right time of year. Each canyon has different locations and times for the best light, but a general rule is that good light is when the sun is highest overhead, in the late spring through early fall. Some special situations, such as light shafts, can only be photographed at specific times of the day and year.

|

|||

| Info: Chromira digital print of Provia 100F 4x5 chrome, Fuji Crystal Archive CD paper | |||